Read the entire article at the LA Times.

What’s the most innovative year ever for rock ’n’ roll? Fans, critics and academics have any number of watershed years they can point to in the more than six decades of post-World War II popular music broadly defined as rock.

There’s 1954, the year Bill Haley & His Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” signaled the flashpoint of rock ’n’ roll, and Elvis Presley first stepped up to a microphone at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studio in Memphis, Tenn.

Or 1964, the year Beatlemania exploded around the world and the launch of the British Invasion.

Don’t discredit 1967, with the Summer of Love, the blossoming of flower power and psychedelic music.

Some stand by 1977, which saw the arrival of that “young, loud and snotty” music called punk rock.

The beginning of the modern era perhaps took flight in 1982, when Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message” put rap music on the national map.

More recently, the case be made for 2001, which gave us the birth of iTunes and redefined — as well as broadened — how we listen.

Terms such as “best,” “most enlightening” or “most important” are all very subjective, of course. But 50 years down the line, a case can be made that 1966 may have been the single most creatively expansive year of all.

That was the year that “rock ’n’ roll” morphed into “rock,” the year that the 45 rpm single yielded to the 33 1/3 rpm long-playing album as the dominant medium for the music and the year that social and political issues became a regular topic of exploration among musicians looking beyond the next hit and aiming to exert a real impact on the world around them.

While rock ’n’ roll was already an established art form, 1966 was the year in which release after release challenged not just artists but also their fan bases. It’s the year, said Jason Hanley, vice president of education at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, that opened up a “whole new vista of promises of what rock ’n’ roll could be.”

Those vistas are visible and audible throughout Bob Dylan’s expansive double album “Blonde on Blonde,” and in the unguarded autobiographical themes and orchestral sonic territory that Brian Wilson mapped out in the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds.”

They’re exhibited in the technological and musical advances of the Beatles in “Revolver,” perhaps the band’s most thoroughly inspired collection of songs ever, and they can be found in the anarchic, boundary-bending of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention’s “Freak Out!”

It’s a never-ending list, and one that locally spawned some notable works, including the raucous energy and unfettered emotional sensibility of singer-songwriter Arthur Lee and his integrated L.A. rock band Love’s debut album, “Love.”

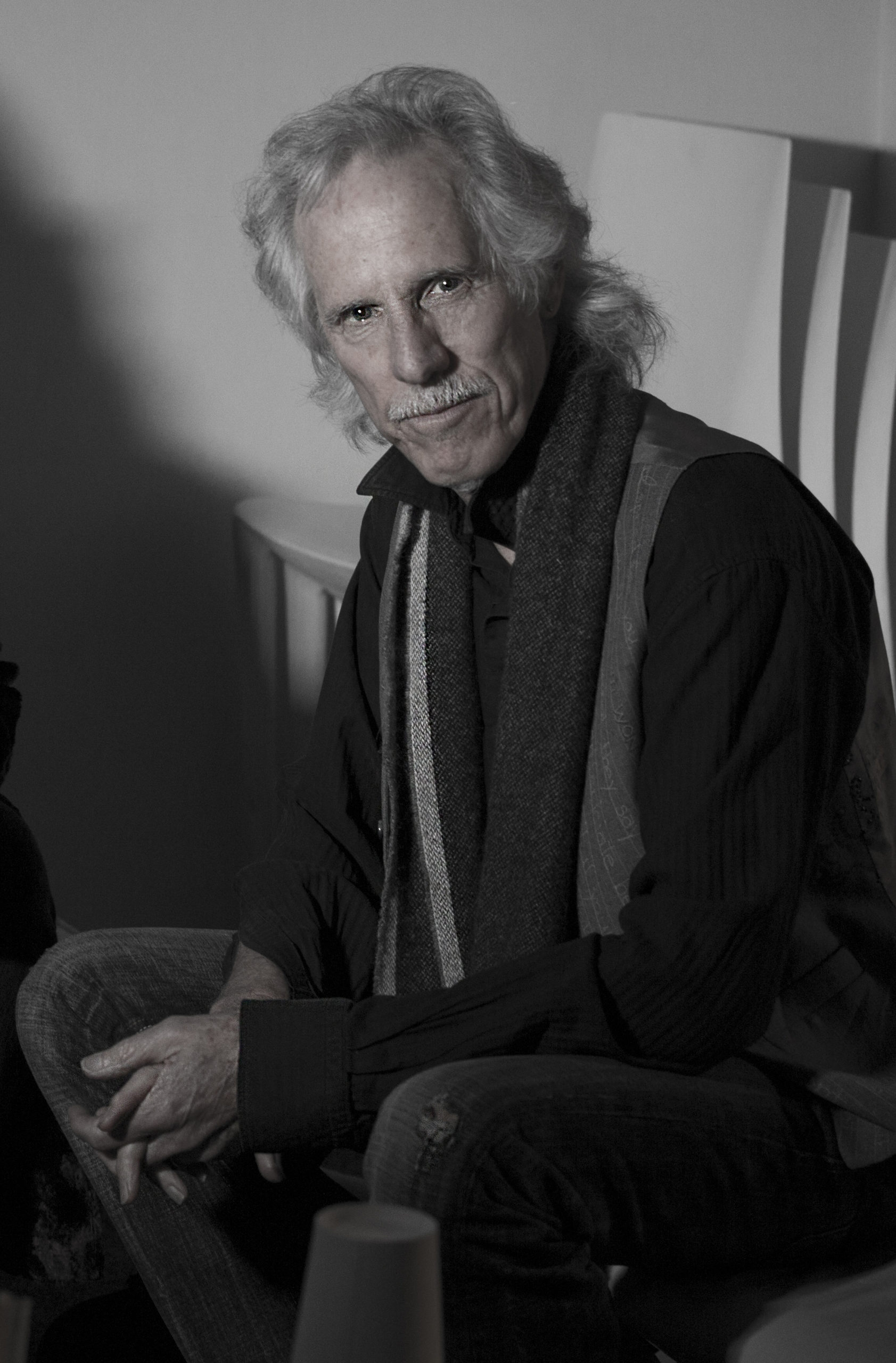

“I always say the ’60s, they didn’t start until ’65, and they ended after ’67,” said drummer John Densmore, founding member of the Doors, which recorded its debut album in 1966. “Before ’65, it was the end of the ’50s; by ’68, pop music was going to cocaine and heroin and burnout and the dream was getting a little ragged.”

Fifty years on, the happenings of 1966 stand for much more than nostalgia. Psychedelic music and country rock, as well as social and political protest music and the incorporation of ambient sounds and effects, not to mention the increasingly accomplished exploitation of studio recording techniques, are all still in play today.

English music historian and pop culture observer Jon Savage makes the case for the year’s pivotal developments in his latest book, “1966: The Year the Decade Exploded,” which navigates through seismic shifts that occurred that year not just in pop music, but also in film, theater, television, art and society in general.

“People think that a critical and rebellious youth culture began with hippies and the underground press in 1967,” Savage writes in the book’s introduction. “In the music press from 1966…almost all the ideas and attitudes that would define the remaining years of the decade are in place: the Love generations, opposition to the Vietnam war, critiques of youth consumerism, an alternative society, a new world as yet unmade.”

Indeed, the escalation of the Vietnam War in 1966 — inductions into the U.S. military jumped 50% from 1965 to 1966 — powerfully shaped political discourse in the U.S. and fueled the rising antiwar movement.

Musicians more and more frequently turned to political and social themes, which showed up in songs as varied as the Beatles’ “Taxman,” the Fugs’ “Kill for Peace,” Junior Wells’ “Vietcong Blues,” Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler’s hyper-patriotic “Ballad of the Green Berets” and even the Monkees’ 1966 debut hit, “Last Train to Clarksville,” a peppy pop-rock hit sung from the perspective of a soldier shipping out to war.

“Normally, you think of the albums that came out in ’67: ‘Sgt. Pepper,’ but ‘Revolver’ was one of the most important albums of that period,” said veteran rock disc jockey Jim Ladd, one of the pioneers of what came to be known as underground free-form FM radio in the late 1960s and 1970s, and who now hosts a free-form show weekdays on SiriusXM satellite radio.

“Revolver” contains everything that made the Beatles the most influential rock act of the 1960s, if not ever. There are hit singles (“Yellow Submarine,” “Eleanor Rigby”), innovative songwriting and record production (“Tomorrow Never Knows,” “Good Day Sunshine,” “She Said She Said”), social and political commentary (“Doctor Robert,” “Taxman”), as well as thoroughly disarming melodic and lyrical creativity (“Here, There and Everywhere,” “Got to Get You Into My Life,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” “For No One”).

“That’s really where I saw the psychedelic change come into the Beatles, more so than ‘Sgt. Pepper,’ which kept it going,” Ladd said. “When you get ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and ‘She Said She Said’ and ‘Taxman,’ I listened to those for the first time and just thought, ‘What?!’ I really was blown away — I could not believe what I was hearing. It was revolutionary.”

Meanwhile, the continuation of Cold War brinkmanship that left teens and young adults existentially uncertain about the future was referenced by the Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out.” The song was released separately as a single with “Day Tripper,” and it became one of the biggest hits of 1966, containing the line, “Life is very short, and there’s no time for fussing and fighting, my friend.”

The Beatles were also part of another critical juncture in rock music that occurred in 1966: After the final date of their third U.S. tour on Aug. 29, the quartet opted out of playing live. Despite the excitement — and lucrative paychecks — from packing tens of thousands of screaming fans into sports stadiums across the country, the band members said the thrill they’d enjoyed in their early days playing for live audiences was being lost amid the roar of the crowd.

Following the lead of Beach Boys creative leader Wilson the previous year, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr decided to focus their efforts on what boundaries they could push by working exclusively in the recording studio with their primary collaborator, producer George Martin.

The departure of the world’s most popular rock group from the concert stage came barely a month after Dylan also went on a long hiatus from public appearances following a motorcycle accident in Upstate New York.

In both cases, they emerged with recordings reflecting dramatic new directions: the Beatles with “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” the following June and Dylan nearly 18 months later with the country-folk album “John Wesley Harding.”

The Rolling Stones also stretched their creative wings in their 1966 album “Aftermath,” moving beyond their core sound of guitar, bass and drums in such future Stones standards as “Paint It, Black,” “Under My Thumb,” “Lady Jane” and “Stupid Girl.” Among the Stones’ 1966 hits were “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Mother’s Little Helper,” both exploring dysfunction and anomie lurking beneath the surface of carefully polished middle-class veneers.

The Kinks likewise demonstrated they were a group on a par with the Beatles and Dylan with their exquisitely literate ’66 album “Face to Face,” which included the hit social commentary single “Sunny Afternoon.”

And although not widely known among music fans, but attaining nearly legendary status among other musicians, Wilson spent the latter half of 1966 working intensely on an even more musically ambitious follow-up to “Pet Sounds.” That album, “Smile,” however, was shelved because of arguments within the Beach Boys and resistance from the group’s label, Capitol Records, to the radical new direction Wilson wanted to take the group.

Such recordings had a profound impact on the rock community, said the Doors’ Densmore, inspiring many musicians to push the envelope well beyond what had been commonplace in 1964 and ’65.

“At the end of ’65, we became the house band at the Whisky [A Go-Go in Hollywood],” Densmore said. “We met and played with every major band you can think of. It was very, very inspiring.”

In fact, Los Angeles in 1966 became one of the most vibrant cauldrons of rock music talent in the world. It was the nexus where Canadian rocker Neil Young and bassist Bruce Palmer connected with guitarist Stephen Stills, singer-songwriter Richie Furay and drummer Dewey Martin to create Buffalo Springfield, one of rock’s most highly regarded new arrivals of the 1960s.

Additionally, Otis Redding’s four-night stand at the Whisky in 1966 helped widen the scope of music out of the Sunset Strip scene, which was dominated by white rock bands. Redding’s incendiary performances drew stars such as Dylan, Van Morrison, Stills and members of the Doors, among many others.

Soul music itself took a major leap forward in 1966 when Aretha Franklin left Columbia Records and signed with Atlantic Records, where she crucially teamed with producer Jerry Wexler and found the supportive environment and artistic encouragement that soon led to her crowning as the Queen of Soul.

Equally important, Jimi Hendrix, who had honed his skills as a guitarist backing other acts including Little Richard, B.B King and Sam Cooke, in 1966 formed the Jimi Hendrix Experience with bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell, a trio that quickly became a game-changer in rock music.

“I saw Hendrix just after he’d come back from London,” Densmore recalled. “All the musicians knew here was something good. It was like someone from Mars, just astounding. At the time, black musicians had Afros and they were playing funk, then this guy comes along playing folk-rock electric guitar upside down and left-handed with two white guys. Everybody knew: This is it. He was undefinable.”

It’s just another instance of one of rock’s most explosive years.

“It was right on the cusp of all these big changes, and we were there,” Densmore said of 1966. “It inspired us to be as good as possible.”